More than 20 years after scientists first released the draft sequence of the human genome, the book of life has undergone a long overdue rewrite.

A more accurate and inclusive version of our genetic code was published Wednesday, a major step toward a deeper understanding of human biology and personalized medicine for people of a wide range of racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Unlike the previous reference — which was based largely on the DNA of a single mixed-race man from Buffalo, with input from a few dozen other individuals, mostly of European descent — the new “pangenome” combines complete genetic sequences from 47 men and African Americans, Caribbean islanders, East Asians, West Africans and South Americans. including women of diverse origins.

The revised genome map is a critical tool for scientists and clinicians hoping to identify genetic variations associated with disease. Researchers say it promises to deliver treatments that benefit all people, regardless of their race, ethnicity or ancestry.

“It’s been needed for a long time — and they’ve done a great job,” said Ivan Birney, a geneticist and deputy director general of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory, who was not involved in the effort. “This will improve our fine-grained understanding of variation, and then that research will open new opportunities toward clinical applications.”

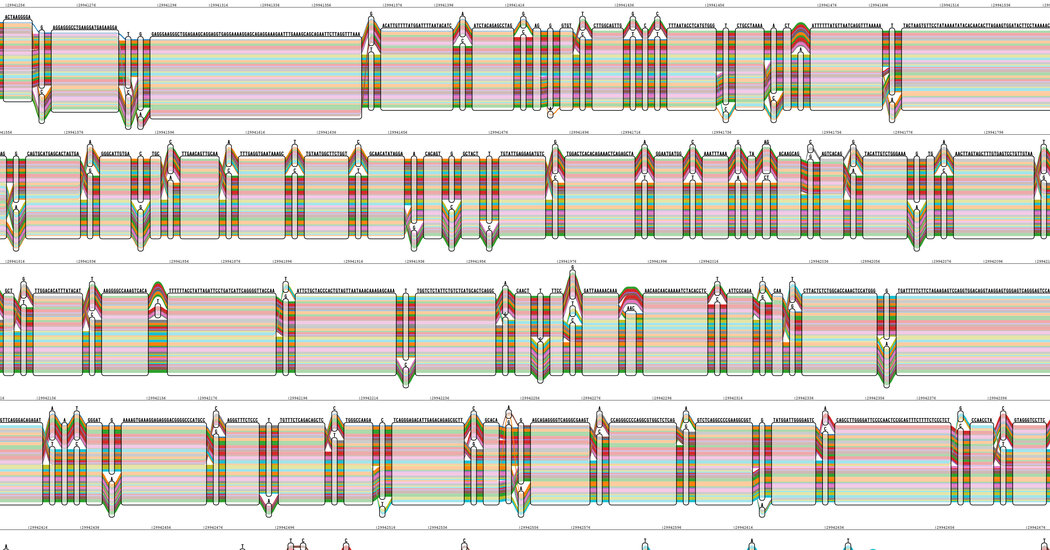

Powered by the latest DNA sequencing technology, Pangenome brings together all 47 unique genomes into a single resource, providing an even more detailed picture of the code that powers our cells. The gap in the previous reference has now been filled, with about 120 million previously missing DNA letters added to the three-billion-letter-long code.

Gone is the idea of a totemic strand of DNA that stretches six feet when uncoiled and stretched in a straight line. Now, the rebooted reference resembles a corn maze, with alternate paths and cross paths that allow scientists to explore the vast array of genetic diversity found in people around the world.

Dr. Eric Green, director of the National Human Genome Research Institute, the government agency that funded the work, likens Panganome to a new kind of bodywork manual for auto repair shops. Earlier, every mechanic had the same design specifications for the car, now there is a master plan covering different makes and models.

“We went from having one good blueprint for Chevy to now having blueprints for 47 representative cars from 47 different manufacturers,” he said.

Knowing what to do with this Kelly Blue Book of Genomics involves a steep learning curve. New analytical tools are needed. Coordinate systems must be redefined. Widespread adoption will take time.

“The task is to make it accessible to the community,” said Heidi Rehm, chief genomics officer at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the project.

But experts say that in due course, pangenome could revolutionize the field of genomic medicine.

“We’re really going to benefit from understanding ourselves as a species, the more the better,” said Evan Eichler, a genome scientist at the University of Washington. Dr. Eichler is one too.

The project’s architects continue to add more population groups, aiming to include at least 350 high-quality genomes covering much of global human diversity.

“We want to represent all branches of the human tree,” said Ira Hall, a geneticist who leads the Yale Center for Genomic Health.

Some of the new genomes come from New Yorkers who previously participated in a research program at Mount Sinai Health System. If their primary DNA data reflects certain underrepresented genetic backgrounds, those individuals will be invited to participate in the Panganome project.

Some gaps will never be plugged in a publicly available reference, though — by design.

Previous attempts to capture human genetic diversity have often extracted sequence data from marginalized populations without considering their needs and preferences. Informed by those ethical missteps, pangenome coordinators are now collaborating with local groups to develop formal policies around data ownership.

“We’re still dealing with the issue of indigenous and tribal sovereignty,” said Barbara Koenig, a bioethicist at the University of California, San Francisco, who is involved in the project.

In Australia, researchers are combining the DNA sequences of various Aboriginal peoples into a similar repository that will be linked to the open-source panganome, but then kept behind a firewall. According to Hardeep Patel of Australia’s National Center for Indigenous Genomics in Canberra, the scientists plan to consult with community leaders about how to access the data by request.

Some local advocates want to see the Panganome project go forward. Keolu Fox, a genomics scientist at the University of California, San Diego who is of Native Hawaiian descent, advises training the next generation of Native scientists to have more agency over genomic data.

“It’s finally time we decentralize power and control and redistribute it between communities,” Dr. Fox said.

#Scientists #unveiled #diverse #human #genome